.com

Estd. 2020

Approved by the Shaw Family

The Royal Hunt

Of The Sun

"I am a bastard and a soldier of Spain "

"Shaw was a troublemaker, he loved to get people riled up." - Carl Gottlieb

trailer

Robert Shaw as Francisco Pizarro (1471-1541)

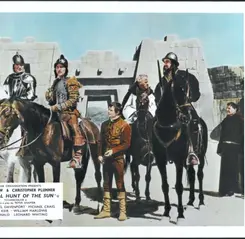

In 1532, Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro leads an expedition into the heart of the Inca Empire and captures the Incan Emperor Atahualpa and claims Peru for Spain.

Directed by Irving Lerner

Screenplay by Philip Yordan from the play by Peter Shaffer

Produced by Eugene Frenke and Philip Yordan

Music by Marc Wilkinson

Cinematograhy by Roger Barlow

Edited by Bill Lewthwaite and Peter Parasheles

Also starring Christopher Plummer, Nigel Davenport and Leonard Whiting

Released by Cinema Center Films

Release Date: October 6th 1969

Running Time: 121 minutes

Location(s): Madrid, Sevilla, Granada and Almeria, Spain and Peru

Filming commenced May 2nd 1968

gallery

The Royal Hunt

Of The Sun

the gold vault

The Royal Hunt

Of The Sun

Soundtrack

A selection of music composed by Marc Wilkinson.

Rare Featurette

Very rare featurette on location in Peru.

Rare Featurette

Very rare featurette on location in Peru.

Rare Featurette

Very rare featurette on location in Peru.

![now showing GIF_thumb[1].gif](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/51f4b8_c475c3f62240416ea489b9651df68e26~mv2.gif/v1/fill/w_512,h_119,al_c,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,pstr/now%20showing%20GIF_thumb%5B1%5D_gif.gif)

The Royal Hunt

Of The Sun

Press Play

The Royal Hunt

Of The Sun

DIRECTOR

Irving Lerner

(1909 - 1976)

"Shaw plays Pizarro with a marvellous mixture of arrogance, innocence and weariness ".

Christopher

Plummer

(1929 - 2021)

Leonard

Whiting

(1950 - )

Nigel

Davenport

(1928 - 2013)

Andrew

Keir

(1926 - 1997)

William

Marlowe

(1930 - 2003)

Michael

Craig

(1928 - )

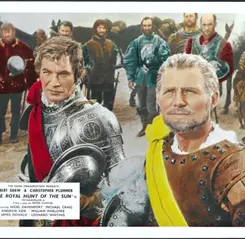

Robert Shaw and Christopher Plummer are two actors unafraid of going big, and both do some serious ACTING in this adaptation of Peter Shaffer's play. Shaw can raise the rafters with the best of them and does so frequently as the leader of explorers invading Peru in order to claim the country for Spain.

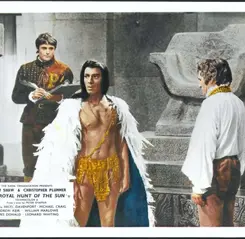

Plummer, meanwhile, plays the Incan King with a high voice, making animal noises, talking to himself, singing, and breaking into warrior dances.

For the first few minutes of this spectacle, one is tempted to laugh but to the actor's credit, he manages to convey the character's naivete and unique form of intelligence very well, and we come to accept this interpretation as a daring and fearless choice that largely pays off.

As for the film, its stage origins are often obvious, but it's difficult to argue with Shaffer's stance on the destructive hypocrisy of Christianity and the way it tainted societies that did not require this form of "order". Not really an adventure or a spectacle, this is a well-acted drama that does require some patience but is worth that investment.

Lobby Card Gallery

The Royal Hunt

Of The Sun

“I enjoy acting, particularly when we are dealing with a subject as searching as, say, A Man for All Seasons or The Royal Hunt of the Sun. Playing Pizarro, in the latter, was very absorbing. He was quite an incredible man, and Shaffer’s words are like fine wine.”

– Robert Shaw

Shaffer’s Pizarro is a mess of a man; a rabidly ambitious seeker, who is unable to bear the thought of retirement or the threat of an ordinary demise, he begins his conquest at an age when most soldiers would have long settled down. Yet his journey in the play is not from poverty to wealth, nor from obscurity to importance, but from lovelessness to love. It’s the last thing he expected to find on his voyage, and it shakes the core of his being.

The actor immersed himself in Pizarro’s life before filming began, but resisted any temptation to let his own resultant admiration colour this ruthless character, whom the viewer must never be moved to love. Shaw gives a courageous and truthful performance, showing the conquistador’s conflict and escalating torment, the extremes of love and hate both passionately enacted.

And for all that his portrayal is so grandiose, there are small and sublime details as well, like the tension in his face that slackens when he speaks with Atahuallpa, and the involuntary movement of his hand to his chest as the garrote does its work; it lasts for only a moment, and in that moment Pizarro’s heart breaks.

Pizarro is a creature of contradictions, capable of both great clarity and tremendous blindness, and so it’s fitting that he bonds with the Sapa Inca over mutual ruthlessness and hatred, laughing freely together over the opponents they’ve slain and those they would kill, the priests they disdain and the dogma they despise. Yet through this kinship, Pizarro rises for a brief time above such considerations, and dares to seek a glimpse of whatever higher power might speak through Atahuallpa.

When his “God” fails to rise again, Pizarro sees Atahuallpa for what he truly was – “what else is a God but what we know we can’t do without?” – and finally understands that he has killed the very ecstasy through which he tasted any real divinity that might exist.

What remains to him is an empty idol: not only the shell of his departed spiritual-son, but the wisp of smoke that rises from his own extinguished fire, the fire of his searching and longing. He is left alone with a fortune that lacks value, a conquest stripped of victory, and a death which fells both his foes and himself for, as Martin’s parting words indicate, the best part of Pizarro dies on that final morning.

What’s perhaps most moving in the cynical, raging journey of Pizarro is that he comes to feel a love so strong it destroys him, and yet this adoration blossoms and then breaks him without ever being professed.

Shaw plays Pizarro with such restless vigour – suffused with an energy like the quivering of a taut string, his own hated mortality always shadowing him – that the limpid stillness he finds in Atahuallpa’s company reveals his heart without any need of words. But the ravages of his life are never far from him – the grinding poverty, the casual scorn, the mockery and dismissal that drive him not only to prove himself, but to exceed the exploits of every explorer before him – and in the end, Pizarro cannot be any more than what he is. And so the die is cast, and the tragedy inevitable.